by Efram Sera-Shriar

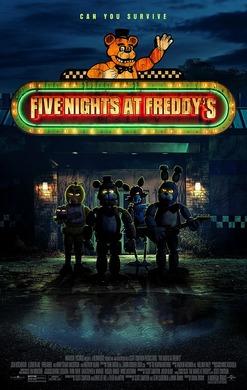

Horror-themed videogames are some of the biggest blockbusters of the industry today. Franchises like Resident Evil have sold over 150 million units worldwide. To a large extent many people come to learn about and love horror through videogames. Take, for example, the recent Hollywood adaptation of the popular videogame franchise, Five Nights at Freddy’s. In the videogame, the player is a night employee at a fictional children’s restaurant called Freddy Fazbear’s Pizzeria, which is loosely based on the real restaurant chain, Chuck E. Cheese. Much like at Chuck E. Cheese restaurants, Freddy Fazbear’s Pizzeria has life-size animatronic characters that resemble anthropomorphised animals. The difference, however, is that at night these fictional robots are allowed to roam around the restaurant freely as a way of keeping their mechanisms from tightening up. The night employee’s job is to watch over them. However, the player soon learns that these animatronic characters have murderous tendencies, and the aim of the game is to survive the night while these crazed robots try to kill you. Fans of the videogame series had been begging for a film to be produced for ages. They were not disappointed, and a cinematic version was released by Universal Studios around Halloween in 2023, which grossed over 200 million dollars at the box office worldwide.

Theatrical post for Five Nights at Freddy’s

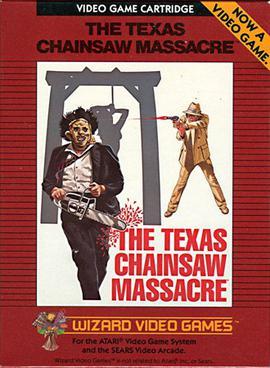

There is a long history of horror-themed videogames dating back to the late 1970s. Many of the early horror releases were based on popular films. One of the first survival horror games is Nostromo, which was produced by the Japanese developer ASCII Corporation in 1981. Made for NEC 2600 home computers, Nostromo was based on the classic science fiction horror film Alien from 1979. As the 1980s rolled in, other horror-themed videogames were developed for the Atari 2600 home console. In 1983, Atari released both The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, which was based on the gory slasher film by the same name from 1974, and Halloween, which was based on John Carpenter’s cinematic masterpiece by the same title from 1978. Atari received lots of backlash at the time due to the violent gameplay of these two videogames. Many retailers refused to sell the cartridges at their stores, and those who did often kept them behind the counter so that they were only available via request. As a result, the sales for both of these games struggled. Wizard Video, the developer behind both of these Atari games, nearly went into bankruptcy and essentially stopped making videogames after these two releases. Today, the cartridges for both The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and Halloween are highly sought after by collectors as a result of the limited numbers that went into circulation.

Box Art for Atari’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, 1983

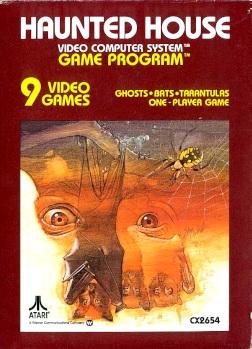

There were also horror videogames that were not based on film adaptations. One of the more famous horror-themed videogames from the early 1980s is another Atari classic, Haunted House. The game’s manual even included a backstory for players to read. Set in a dilapidated mansion in the fictional town of Spirit Bay, locals had witnessed all kinds of strange occurrences at the property, including hearing eerie sounds and heavy footsteps when no one else was around, and seeing shadowy figures looming in the garden or by the windows of the home. It turns out, the property is haunted by the former owner Zachary Graves, who died in the 1890s as a result of an earthquake. His spirit is sustained by a magical urn inside the house, which is an old heirloom of the Graves family. To make matters worse, the urn was broken during the earthquake and the pieces were scattered throughout the mansion. The only way to bring peace to the property, and allow the spirit of Graves to move on, is by finding the pieces and putting back together the urn.

Haunted House’s backstory, aesthetic, and packaging represents a wonderful example of classic popular occulture. The box art features familiar gothic, horror, and occult references. We have the three hanging bats, which is a nod to popular vampire stories like Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Stephen King’s ‘Salems Lot, as well as cult cinema favourites such as Nosferatu and Lust for a Vampire. A poisonous spider with a web also features on the box, and it is a common visual motif in many gothic works. Of course, the wide and frightened eyes prominently displayed in the background of the box art, mirrors the sort of terrified expressions seen throughout horror and occult-themed media.

Box art for Atari’s Haunted House, 1982

In the game the player is represented by a pair of eyes and must make their way through the various pitch-black rooms of the mansion in search of the urn pieces. There are three to collect. Unfortunately, the player is also locked inside the home and can only get out if they find the key as well. As the player navigates the various floors of the mansion, they need to avoid all kinds of enemies from giant spiders and bats, to floating spectres. At the time of its release in 1982, Haunted House was considered to be one of the most immersive videogames ever made. A reviewer for the well-known magazine Electronic Games wrote in 1983 that Haunted House’s ‘audio/visual trimmings are excellent and give the arcader the spine-tingling sensation that something spooky is always about to happen.’ By early 1980s videogame standards, Haunted House’ graphics and gameplay were fantastic. Nowadays, though, most gamers would find it visually dull and clunky. That said, it remains a frustratingly tough videogame to play.

Gameplay from Atari’s Haunted House, 1982

The 1990s brought gamers some of the most loved horror franchises ever made, including some of the best instalments of the vampire-themed platform series Castlevania, and the original release of the Resident Evil franchise in 1996. Other popular horror-inspired videogames from the decade include the amazing adventure horror game Phantasmagoria from 1995, and my personal favourite, the demonic masterpiece Diablo, developed by Blizzard Entertainment in 1998. There have since been three more instalments of the Diablo series, with more intricate storylines, and darker artwork, music, and themes. The most recent instalment Diablo IV was released in 2023 to much fanfare. Hilariously, it generated 666 million dollars in revenue within only five days of its launch. This is a powerful reminder of how significant videogames are as a key conduit of popular occulture among mainstream audiences worldwide.

Horror videogames continue to be some of the best-sellers in the market today, and still hold close ties to the film industry. Sometimes the games are based on a film, other times, the film is adapted into a game. One thing is clear, horror videogames are a major part of our culture and represented one of the most popular forms of horror entertainment in our modern world. While many of the original horror videogames were fairly simple, and not particularly frightening, nowadays horror franchises like Five Nights at Freddy’s are designed to scare you out of your chair. They are insanely immersive and utterly terrifying. We should all look forward to what the horror videogame industry has in store for us next.

Box Art for Nintendo’s Super Castlevania IV, 1991.

REFERENCES

- Anonymous, Haunted House: Atari Game Program Instructions, (Atari Inc., 1981).

- Anonymous, ‘Haunted House,’ Electronic Games 1983 Software Encyclopaedia, 1 (1983). p. 25.

- Ewan Kirkland, ‘Gothic Videogames, Survival Horror, and the Silent Hill Series,’ Gothic Studies, 14 (2012), pp. 106-122.

- Bernard Perron, Horror Video Games: Essays on the Fusion of Fear and Play (McFarland and Co., 2014).

- Bernard Perron, The World of Scary Video Games: A Study in Videoludic Horror, (Bloomsbury, 2018).

- Dawn Stobbart, Videogames and Horror: From Amnesia to Zombies, Run! (University of Wales Press, 2019).

Faye Zuckerman, ‘Games from Ripley’s? Believe It!,’ Billboard, (6 August 1983). p. 25.